The opening of Tate Britain’s Sargent and Fashion exhibition is more than an opportunity to view some of the most famous portraits in the world: it’s an invitation to spend time with people who began as acquaintances – faces you recognised, who played a perhaps minor moment in your life – and leave having made several roomfuls of dear friends.

There are so many connections between other art-forms and fragrance – music and literature being the most usually cited – but pairing portraiture and perfume was an emotional connection impossible to resist. It’s because (as those of us obsessed with fragrance readily understand, and which anyone can feel deep inside when a certain smell triggers an emotional response within them;) a scent can communicate with such aching, soul-baring intimacy; telling complete strangers things about ourselves that we’d never otherwise overtly express.

Partly, the intimacy one feels in Sargent and Fashion comes from seeing the paintings up close and in person. The way these people (mostly women, in this exhibition) meet your eye, often challengingly, or sometimes deliberately evading your gaze. Intimacy, too, in the way he painted them – mostly these people were very close friends within Sargent’s social circle, and this fact absolutely leaps off each canvas in the vivacious vibrancy and liveliness with which they’re depicted. There’s tenderness at times, and humour, too. A vulnerability or a twinkle in the eye that can only be achieved through decades of a deep bond between painter and sitter.

We, as visitors, get to feel truly included in this partnership while viewing the exhibition. And the shortcut to our deeper understanding of the people behind the paint is partly thanks to the clothing and accessories displayed alongside the portraits. Many of them are the very outfits the sitters were wearing while he painted them, and we learn from the exhibition notes and signs beside the displays, that not only did Sargent keep costumes and props in his studio, but that on numerous occasions Sargent designed many of the outfits himself – in collaboration with esteemed couture fashion houses such as Worth. It wasn’t a case of ‘come as you are’ when turning up to Sargent’s studio to be painted. It was far more ‘let’s show these people who you REALLY are.’ As the introduction to the exhibition guide states:

‘Sargent and his sitters thought carefully about the clothes that he would paint them in, the messages their choices would send, and how well particular outfits would translate to paint. The rapport between fashion and painting was well understood at this time: as one French critic noted, ‘there is now a class who dress after pictures, and when they buy a gown ask ‘will it paint?’’’

At this point I have to allow myself a rant. Not about the exhibition – which I adored, and which I shall think about for many years to come – but about some of the reviews by art critics I’ve read since attending the Press View. In their opinion, the extraordinary artefacts detracted from the portraits and were entirely unconnected to our understanding of Sargent or the sitters. They describe the clothes and accessories, variously, as ‘old rags’ and ‘glittery baubles’, or ‘belonging in Miss Havisham’s attic’. And the undercurrent of these reviews very strongly comes across as ‘these are women’s fripperies, therefore utterly bereft of meaning or importance.’

To arrive at this conclusion is – quite apart from being disgustingly misogynistic, and in the same patronising lineage as literary critics dismissing Jane Austen’s work as historic ‘chick lit’ because it dares to document the lives of women – to miss the point of the exhibition entirely. The clue was in the name, after all: Sargent and Fashion. The clothing was even capitalised in the title to help them.

Women have always been especially judged on what clothes they wear, and in this exhibition the point is made – again and again, if you care to comprehend – that the sitters and Sargent liked to subvert this power play in the colour and cut of the clothing, in the positioning of their bodies. They were judged for these choices contemporarily, too – several of the portraits causing shocking scandals and what we’d now understand as ‘being cancelled’. Most notably with the famous (and swoon-worthy) portrait of Madam X, for which, as this brilliant Varsity article on the infamous portrait explains:

‘Sargent initially depicted Gautreau in a tightly silhouetted black gown, with chained straps doing very little to conceal her pearlescent shoulders and décolletage. In fact, originally, Sargent chose to drape one strap down Gautreau’s arm; this inadvertently caused further outrage. To spectators past, it was a brazen attempt to barely veil Gautreau’s body, suggesting that if one strap can breezily slip, so can the rest.’

The clothing has nothing to do with the portraits? No importance? Tell that to Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, who was lacerated by public opinion to the point where, as the Varsity article recounts:

‘Even Gautreau – a woman fiercely aware of her beauty, and inclined to weaponise it for advancement by becoming the archetypal ‘Parisienne’ – felt that it was best to anonymise her painted figure: thus Madame X was born.’

These spectacularly cloistered critics failed to appreciate the importance Sargent himself placed on the clothing – let’s reiterate the fact he DESIGNED many of the outfits himself, or carefully positioned the clothing and angles we can view them from; choosing to deliberately drape and conceal, or otherwise starkly reveal his sitters. And little wonder they missed (or elected not to place value on) the many examples of how important these clothes were – they spent very little time actually looking at the portraits or the clothes, or the numerous signs next to them explaining the significance. Instead, they gathered in tiny, tutting cabals during the exhibition, loudly discussing which other exhibitions or parties they had, or had not, been invited to.

#notallmen, but sadly, the ones I saw doing this all were. Ironically, I overheard them discussing what outifits they were going to wear to various fashion event parties that evening. But these were their clothes – men’s clothes – so presumably were of significance to them.

I shan’t link to their excoriating yet ultimately vacuous reviews because it lends them more credence than they’re due. And I needn’t couch my words, because they’ll never bother reading something so frivolous as an article matching PERFUME to portraits. Fragrance, I feel pretty confident in assuming, is something they would similarly sneer at as being bereft of cultural and emotional value, so equally pointless in examining. Those of us who feel otherwise are lucky in having our lives enriched by art in more ways than they could ever comprehend.

Let’s allow them to tut away to their heart’s content, and instead go and see the exhibition, and then imagine if we knew what fragrances the people in these portraits had also chosen to wear! Or what scent they might select, were they around now. Such consideration adds further layers which might reveal depths even Sargent never got to know. Which perhaps they never even truly realised about themselves.

Fragrance can do that. The right scent, worn at the right time, can disclose intimate secrets or conceal us in a cloak of intrigue. A perfume can be a worn as a kind of emotional X-Ray, or played with like choosing a costume from a dressing-up box.

The women in these portraits, we learn (and FEEL by smiling along with them), were not passive, wilting muses – they were accomplished artists, poets, academics, and philosophers in their own right. And they were in partnership with Sargent, with the fashion designers, and with us as we look at them and feel something that goes beyond the gaze to a complicit understanding. Just as wearing a particular fragrance can announce to the world who we are inside, or dictate how we want others to feel about us – transcending words and going straight to the soul.

When we take time to select a scent based on our emotional response to it – or gather whole wardrobes and toolboxes of them – we go beyond passive consumers to being in a relationship with the perfumer, the packaging designers, the experts and consultants that recommended them, and the people who then smell that fragrance as we waft past.

In pairing perfumes with Sargent’s portraits, then, I hope it helps you feel an even closer companionship to the people portrayed in them, and a have deeper understanding of the mood each scent can similarly evoke. And I urge you to try this for yourselves next time you’re in a museum or art gallery – or meeting friends in your own social circle. Wonder how you’d scent them, and then reflect on what this tells you about them, about the fragrance, and even what this reveals about our own levels of perception and interpretation.

Having gained a greater closeness to Sargent the man (not just the painter), and to the people (not only the portraits) during this exquisitely soul-enriching, emotional conversation of an exhibition, I feel he’d have approved. Indeed, he’d likely have had fragrances specially commissioned, worked on exacting briefs for the perfumers, and suggested precise tweaks to the perfumes’ formulae – the better to reflect the people behind the layers of paint, and further shaping our understanding of them.

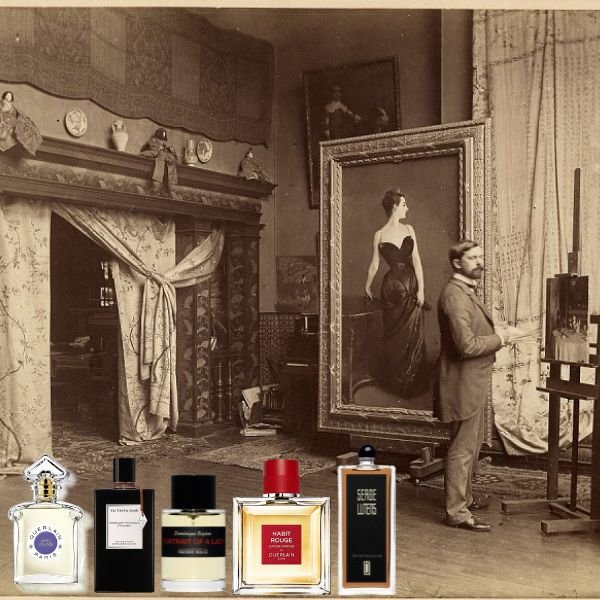

Without such bespoke examples, what follows are the perfumes I felt ‘matched’ the personality of five portraits that particularly spoke to me. Indeed, there were so many other fragrance pairings inspired in my mind (and still bubbling away) by seeing this exhibition, that I’ll need to do a Part Two to stop them invading my every thought. But for now, what I really want to know is – which portraits would you decide to match, having got to know them at the exhibition; how would you scent them, and why would you pick that to evoke their character, the clothing, and the mood of the portrait itself…?

Sargent and Fashion is at Tate Britain until 7 July 2024. [Free for Tate members, and worth every penny if you’re not]

John Singer Sargent Lady Agnew of Lochnaw

Outwardly the very picture of femininity, in both the sitter and the scent there’s a strong backbone that runs through the centre. Gertrude is surrounded by a froth of delicate, transparent material, but she sits on a hard-backed chair and meets us with a direct and judging stare. In Apres L’Ondee a spring garden of rain-soaked blossoms feels encircled by a high fence. The violet in it is cool, almost frosted, but has survived the storm. You may admire the garden, but the casual passer-by will not be invited inside.

Guerlain Apres L’Ondee £108 for 75ml eau de parfum guerlain.com

John Singer Sargent Ena Wertheimer

Sargent and Ena were great friends, their rapport and her amusement vibrating through this unconventional portrait, and the stance apparently all Ena’s doing. She came to his studio, grabbed a broom and began fencing with it. Her heavy opera coat becomes a Cavalier’s uniform (or a witch’s cloak, given the subtext of the broomstick). In Moonlight Patchouli, inky black velvet is suddenly spotlit, bathed in a phosphorescent glow, dusted with iris – a focus on warm skin dominating the darkness.

Van Cleef & Arpels Moonlight Patchouli £145 for 75ml eau de parfum harrods.com

John Singer Sargent Mrs Hugh Hammersley (Mary Frances Grant)

A fashionable hostess of salons, Mary looks so happy to see you, but would like you to understand she has a lot to do. The extraordinary depth of colour and texture in her gown are discussed in this Metropolitan Museum of Art feature, but her vivacity and poised opulence are obvious. I tried not to use this scent in this piece, but it had to be hers. The striking depths of rose, raspberry and patchouli are hugely impactful, filled with beauty, power, and a presence that lasts long after you’ve left a room.

Frédéric Malle Portrait of a Lady from £60 for 10ml eau de parfum fredericmalle.co.uk

John Singer Sargent Dr. Pozzi at Home

A blaze of passionate red, this man might appear a dandy, but he’s incredibly intelligent. He may look casually attired, but the drape of his dressing gown and the meticulous pleats of the white linen shirt dramatically contrast the swathe of scarlet. Habit Rouge is devilishly handsome and knows it. Dynamically woody, a hint of animalic magnetism balanced by almost soapy neroli and jasmine; rendered irresistible by the creamy warmth of spiced vanilla and moody patchouli in the base.

[P.S. I also attempted not to use Guerlain twice in my matches, but the body craves what it needs, and Pozzi’s needed this.]

Guerlain Habit Rouge £81 for 50ml eau de parfum guerlain.com

John Singer Sargent Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau)

The largest space in the exhibition is given over to Sargent’s most famous portrait, room for captivated crowds to gather and gaze, elongating their bodies and arching upwards, echoing her position, desperate for her to turn and look back. Virginie adored this painting, as did Sargent, but her life was scandalised by it. In Santal Majuscule, we’re invited to worship the sandalwood, acres of creaminess suggesting an expanse of bare skin. A pared back elegance which nonetheless skewers with longing.

Serges Lutens Santal Majuscule £135 for 50ml eau de parfum sergeslutens.co.uk

Written by Suzy Nightingale