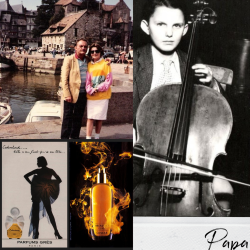

Father’s Day 2023 Tribute to my father Hubert Varron 1933 – 2005 – ©Emmanuelle Varron’s personal collection.

In our family, we have never been really attached to Father’s Day. As it always fell in June, very often at the time of my mother’s birthday (June 15) and very close to my father’s (June 23), we kept the big party (and the gifts) to blow out the candles, and Father’s Day was the opportunity to “rehearse” before. But thanks to Editor-in-Chief Michelyn Camen, I have the opportunity to pay tribute to my father who was a cellist and who would have turned 90 in a few days.

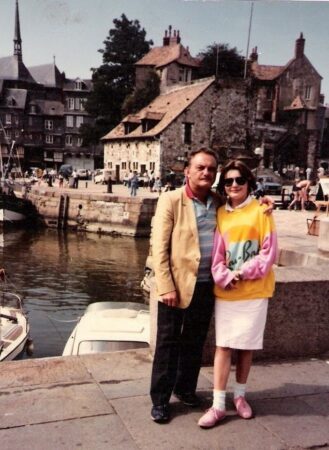

Emmanuelle and her father in Normandy in the mid 80s – ©Emmanuelle Varron’s personal collection.

Clément Hubert Varron was born in Paris on June 23rd 1933, fourth and youngest son of Bernard and Thérèse. Clément for the civil status, but Hubert in real life, because my grandfather had interchanged the first names when declaring his birth at the town hall. Among the many family secrets that surround mine, it seems that there was also a little sister, born after my father, but who died very young accidentally. But my dad never mentioned her. So, four Varron brothers. My grandfather was a civil servant and my grandmother a housewife. I know very little about their history, only that my father kept in him a real trauma of the WW2, as he found himself fleeing Paris with his mother and his brothers to take refuge in the free zone, then hide in the south of France. One of the rare stories that he told me about was his memory of having fled through the roofs after an SS soldier had been shot in front of the building where he lived in Lyon: it was ordered that all residents were to be immediately shot in retaliation. My father remembered the fear, the dizziness he felt up there and the sound of bullets down below. Other “twitches” have also marked him for life: one day as a teenager, as I was very proud to have bought with my own money an ecru T-shirt / pants set with large vertical brown stripes, I was told “Do you think you are in Auschwitz?” accompanied by cold anger. He also believed that it was inconceivable to queue to eat, that it was disrespectful of what had been experienced during and after the war by people who could not eat normally. My father, his brothers and his mother returned safe and sound after the liberation of Paris. I never quite understood what my grandfather’s life had been like during that time; he died in 1956, long before I was born, and that secret was well kept too. I simply know that he had been smart not to declare his family when in 1940 the census of Jews was ordered in France.

Robert Doisneau – Dans le métro – Maurice Baquet et son violoncelle – 1958 -via Getty

My grandfather was a wise man, but also ambitious for his sons: a great lover of classical music, he dreamed of seeing all of them become professional musicians one day. They all chose an instrument. And if Emile, the eldest, quickly found another center of interest for his professional life (photography), Pierre, Michel and Hubert, my father, achieved the paternal dream. My uncle Pierre became a violinist (at the Radio-France orchestra), my uncle Michel a violist (at the Opéra de Paris), and my father a renowned cellist. They also collaborated in the 1940s and 1950s as the “Trio Varron”, playing in Parisian concert halls and French festivals. My father graduated from the prestigious Paris Conservatoire at 15, a student adored by his teacher Maurice Maréchal. Then won the Geneva Prize in 1950. A few months earlier, he had obtained a second prize in Prague, preceded by a certain… Mstislav Rostropovitch. From this musical confrontation remained a few precious Bohemian crystal objects as a reward and a great enmity between my father and the Russian cellist. Mr. Rostropovitch, who was invited to conduct Eugene Onegin in 1982 at the Opéra de Paris (with his wife in the role of Tatiana) had not failed to quarrel with my father over matters of bowing, the latter having a malicious pleasure to pretend not to understand him, arguing his bad French. The witnesses told me of two roosters clashing in the orchestra pit. Because yes, in 1955 (he was then 22), my father entered the Opéra de Paris as a super soloist. If this orchestra was his main employer, he was working much more: he regularly recorded music scores with Georges Delerue, Michel Legrand, Saint-Preux, Francis Lai or Vladimir Cosma (of whom he was the lead cellist), pop albums and TV shows. A few years ago, I was so proud to recognize him in a 1976 TV preview of the renowned musical Starmania, hosted by Michel Berger and Luc Plamondon. Thanks to the Beatles, integrating string instruments into the musical score was very popular. My father lived during the golden age, recording with almost all French singers, and sometimes even international ones. Funny anecdote from the late 80s: my father tells me that he is going to record with two English artists, a man and a woman, whose name he cannot remember. He believes it sounds like “Smiths”, then describes the singer to me: I immediately recognize Annie Lennox. “Dad, you are going to record with Eurythmics, but it’s great!“. He was not so excited as he was so critical; very few artists could find favor in his eyes. When he came back from the studio recording, I couldn’t help but ask him how the session had gone. And he answered me: “Oh, she doesn’t sing badly, for sure. But he (Dave Stewart), he really impressed me: he know about music, you know! “. Part of his habits would also be being dissipated during a recording or a “live” performance. I no longer count the number of times I saw him chatting with his neighbor in front of the cameras and worse, chewing his gum in the orchestra pit: he loved doing that during the harpsichord solos which bored him prodigiously in Mozart’s operas. But he was fearsome with his colleagues when they were trying to do the same.

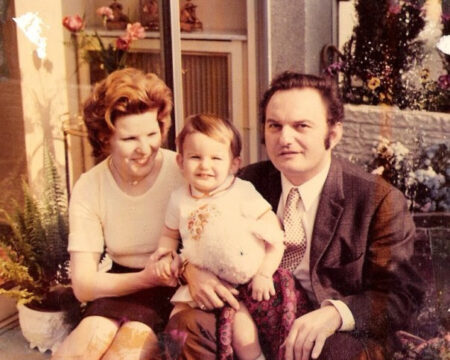

Emmanuelle and her parents in 1975 – ©Emmanuelle Varron’s personal collection.

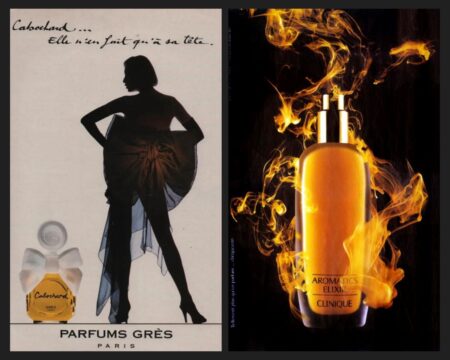

My father was a fabulous artist, a very loving father but he was also a true misogynist. Born before WWII, he had strong ideas about women and their place in society: at home and raising children… as his mother had done so well. He was still living with her when he met mine in 1967. My mum had just arrived from Nancy, in eastern France. She was a manuscript proofreader, a Catholic, had just freed herself from the parental yoke and dreamed of the high life. How did she and my father meet? Simply through a matchmaker. My father was 34 but still single, and my mother 21, innocent and romantic. He found her charming, she was impressed by his talent. He drove an Austin Mini that regularly broke down and she found this cute. And then, he wore Grès Cabochard, which was not common. It was only very recently that I learned of this link between my father and this mythical perfume, originally intended for women. Created in 1959 by Bernard Chant, it is a fragrance that is still available to buy, but in a totally different formula. You can find some vintage versions at auctions (The Fragrance Vault carries the EDT. I had the chance to smell the eau de parfum version, and I can imagine my father wearing this green chypre, where galbanum, patchouli, oak moss and castoreum are magnified.

Grès Cabochard and Clinique Aromatics Élixir advertising – ©Grès and ©Clinique.

I don’t know if he wore it on his wedding day, in June 1969. Or if he was still faithful to it when I was born, in March 1972. My memories of perfumes when I was a child are rare: I remember seeing bottles of Pino Silvestre, Mont Saint-Michel amber cologne, and lots of miniatures that must have come from Chanel, Dior or other major French brands. HIS perfume, the one I remember, and which was his signature until the end of his life, was Clinique Aromatics Elixir (1971, Bernard Chant). Here again, a composition marketed for women. Can you imagine that this fragrance used to be my mother’s? And that my father simply stole it from her, without even asking! He found it so original and pleasant to wear that he immediately adopted it, forcing my mother to find another one (she then navigated between Estée Lauder Cinnabar and Saint-Laurent Opium, to finally adopt Karl Lagerfeld KL). Clinique Aromatics Elixir has been omnipresent in my life: in 1984, when my parents divorced, it was decided that I would live with my father. Thus, I knew this perfume from every angle, smelling it in the early hours of the day in the bathroom, then in the car when my father accompanied me to high school. Its aromatic and flowery notes were then very present. It was the smell of my father in the morning. And then in the evening, when he returned from his performance at the Opéra de Paris, he would systematically kiss me in my bed before going to sleep. There, I would smell more animalic and spicy Clinique Aromatics Elixir, with a pervasive chypre facet that had warmed on the skin all day long. It must be said that my father sprinkled himself with it. He would even put some on his shirts, on the armpits, which obliged him to buy new ones, as the amber color of the juice clung to the white fabric. For many years (and probably influenced by my mother, who was still mad at him and the theft of her fragrance), I tried to explain to my father that he wore a woman’s perfume and that it was weird. I did not have yet a global vision of perfume at that time, of course. He maintained that it was a perfume for men based, logically, on the very sober shape of the bottle, contrary to the usual “feminine” codes. I was particularly proud of myself when, around the age of fifteen, I bought him a Clinique Aromatics Elixir box containing the perfume, of course, but also the shower gel and body cream. I finally had the proof that my father was wrong! I remember he looked at the box in astonishment, then laughed, and said to me: “Well, never mind if it’s a perfume for chicks! It’s mine, and I don’t intend to change it.”

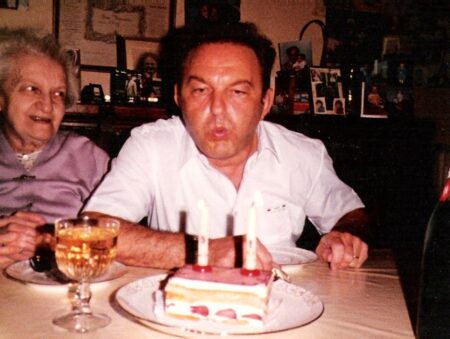

Emmanuelle father’s in 1984, on his 51st birthday with his mother; the same age that Emmanuelle has today in 2023 – ©Emmanuelle Varron’s private collection.jpg

This perfume accompanied him until the end of his life, until August 16, 2005. I have a bottle at home, which I do never touch. I am unable to wear it as I associate Clinique Aromatics Elixir with my father and because my mourning remains difficult given the circumstances of his death and all that followed. Smelling Bernard Chant’s creation in the street gives me a painful heartbeat. However, I realize that despite his very traditional character, very “vieille France” as we say here, Hubert Varron was a bit rebellious when it came to fragrances. And I say to myself that both him and my mother opened my nose to this wonderful world, and that if he were still part of this world, we would share a lot of complicity talking about perfumery as an art.

Emmanuelle Varron, Senior Editor and Paris Brand Ambassador

Follow us on Instagram @cafleurebonofficial @monbazarunlimited

Happy Father’s Day to all who celebrate on June 18. 2024. Our first Father’s Day tribute was Eau de Popsie by Deputy Editor Ida Meister in 2010, Da in 2011 by Mary Beth Devine, Nir Guy of Perfumology in 2019, Former Video Editor Sebastian Jara in 2020, Perfumer Marissa Zappa’s tribute to her father in 2020 and Pissara Umavijani ode to her father Montri in 2021.

Please leave a comment out of respect. What is your first scent memory of your father’s (or father figure) fragrance

This is our Privacy and Draw Rules Policy